It isn’t all aerial imaging and crop surveys; sometimes, people use drones to do bad things. Through a partnership with DroneSec—a private drone security intelligence firm with offices in Australia and Singapore—RotorDrone Pro is able to offer these briefings regarding the nefarious use of small UAS worldwide.

Mavic 2 Shot Down by Indian Military

Incident Type: Surveillance of hostile territory Incident Location: Keram District, India/Pakistan Line of Control in Disputed Kashmir Aircraft Type: DJI Mavic 2 Pro Incident Resolution: Aircraft destroyed by gunfire A DJI Mavic 2 Pro being operated by the Pakistan Army Special Services Group (SSG) was shot down by Indian troops while flying 200 feet beyond the Line of Control that separates the opposing forces in the disputed territory of Kashmir late last year. This incident is one in a series that have involved small, commercial UAS flown by the Pakistani SSG that have crossed over into Indian territory, some intent on delivering weapons and munitions to rebels who oppose India’s control over the region. That does not appear to have been the case in this instance, as the Mavic 2 doesn’t have the payload capacity to carry an assault rifle or a belt of grenades—both of which have been intercepted on previous flights. What it does have is an extremely capable visible-light camera, with a 1-inch CMOS sensor and a 20-megapixel effective resolution, also capable of capturing 4K video. So aerial reconnaissance appears to have been the most likely goal of the mission, or potentially testing India’s ability to detect and respond to an intrusion by a small, and relatively quiet, UAS. Or the goal may simply have been to troll the Indian troops. If this was a reconnaissance mission, it would be interesting to know what Pakistani forces hoped to achieve. Were they simply watching the video link in real time to glean what they could about the location and disposition of Indian forces, or were they attempting to survey the area the same way you or I might map a quarry using Pix4D or DroneDeploy? Looking at the images recorded on the memory card would likely reveal something about the SSG’s goals. If the intent of the Pakistani’s incursion was to test India’s defenses or annoy its soldiers, they got their answer with a bullet, in the most literal sense of the word. India reported shooting the aircraft down, a point amply proven by a pair of photographs that they shared of the wrecked UAS. The images suggest that the bullet entered the rear of the aircraft, passing through the battery and the internal electronics before exiting the front directly below the gimbal. This trajectory would seem to indicate that the shot was actually fired from slightly above the aircraft. This suggests that the aircraft was flying at very low altitude, or the soldier who brought it down was shooting from an elevated position. Another interesting fact is that although there are a few black smudges surrounding the hole in the battery cavity, which suggest the lithium-polymer battery was punctured and caught fire, it seems likely the battery was ejected from the aircraft by the force of the impact. Otherwise, I would expect to see significantly more fire damage.

It appears that the aircraft was hit at least once before the shot that brought it down. The right front propeller has a tidy hole punched through it, which fractured the blade, although the aircraft likely could have continued to fly with this damage. As DroneSec points out in its own analysis of the incident, employing conventional counter-UAS measures, such as radio jamming equipment or interceptor drones, is a difficult challenge given the vast frontier that the Indian army must monitor and defend. Nevertheless, DroneSec’s advice is to develop a standard operating procedure to deal with incursions by hostile drones and train its soldiers to detect them and respond appropriately — an emerging issue for military forces worldwide. For its part, India appears to have already internalized that lesson. Before troops to be stationed on the line of control are sent to their forward operating bases, they must first complete a two-week training course that prepares them to deal with intrusive small UAS.

(Photo by AJ Kashmir)

The Case of the Tattle-Tale Drone

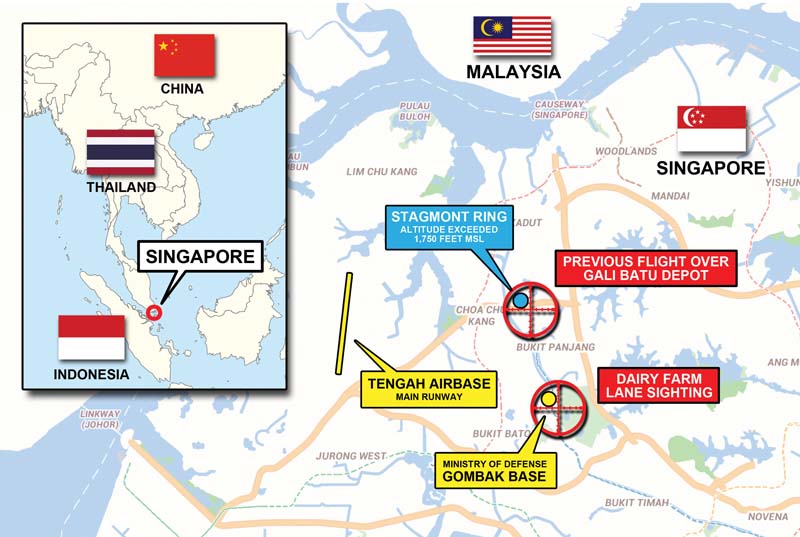

Incident Type: Operation of UAS in restricted airspace Incident Location: Multiple military facilities and depots in Singapore Aircraft Type: Not specified Incident Resolution: Aircraft confiscated, pilot arrested

On October 19, 2020, an alert passerby spotted a small UAS flying near Dairy Farm Lane on the tiny island city-state of Singapore. As that location is within five kilometers of Tengha Airbase, the unidentified individual notified the police. Shortly thereafter, the pilot—Russell Wong Shin Pin, age 20—was taken into custody and his aircraft was impounded. Singapore is famous for its strict judicial system. In 1994, an 18-year-old American citizen, Peter Fay, was sentenced to six strokes with a cane for vandalism. That’s right: a criminal justice system that still has flogging on the books as a penalty for a crime that would likely merit community service in the United States. With that in mind, I couldn’t help but squirm at the thought of the fate that would befall Wong for unlawfully operating a UAS near a military airfield. Fortunately for Wong—and his backside in particular—the sentence for his ill-considered operation could be merely a year in prison and a $15,000 fine. However, that was before law enforcement examined the drone’s telemetry and memory card. On it, they found records of flights over several other military installations, as well as aerial photographs of them. In addition, one flight reached an altitude of nearly 1,800 feet.

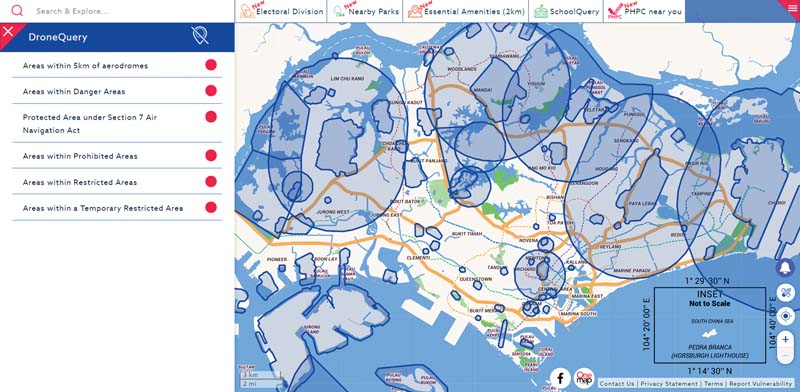

Many aspects of Singapore’s UAS rules closely parallel the standard’s established by the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA), although there are some key differences. First, the default ceiling for flight operations is 200 feet above ground level, rather than the 400-foot standard put in place by the FAA. Like the FAA, Singapore’s civil aviation authorities have established a two-track system of regulations for UAS: one for hobbyists and the other for commercial users. Like the US, both groups are expected to take a written exam to verify their aeronautical knowledge, although professional pilots must also pass a hands-on flight test. In both countries, any aircraft weighing more than 250 grams must be registered.

In Wong’s case, DroneSec commended the police in Singapore for conducting a forensic evaluation of the UAS, thereby revealing Wong’s additional instances of mischief. It further suggested that the country keep a database of launch sites used by miscreants like Wong. Their hypothesis: it is likely a pattern will emerge over time, owing to the local geography or characteristics of the terrain that make those spots conducive for launching and recovering aircraft. DroneSec also recommended the authorities develop standard operating procedures for responding to rogue drones and running drills to test and improve their effectiveness, as well as enlisting the public to report suspicious UAS activity. At the time of his flights, Wong had no training or credentials to his name and disregarded a nationwide map that shows where UAS operations are prohibited—available both online and through a smartphone app—which has been promoted nationwide in a manner similar to the “Know Before You Fly” campaign in the U.S.

In total, Wong is now facing a total of eight charges for violating the Air Navigation Act and the Infrastructure Protection Act. By Patrick Sherman